EMPATHY

The discovery in the 1990’s of mirror neurons in the brain and the subsequent research and books about them in the 2000’s gave me a basis to understand a phenomenon that had puzzled me: why do some people give their lives for others. The new theory is that when you see someone in pain, pain neurons in your brain light up, not your actual pain neurons, but mirror neurons that echo the pain. This is, it is posited, one of the reasons we can have empathy. When we see someone enjoying an ice cream cone, our brains light up as if we were enjoying it too. When my children were sick, I would feel their same symptoms, but in a way that I knew was only in my imagination because I wouldn’t vomit or have a temperature. Bill discovered that if we put the sick child in bed with me, they would feel better, their temperature would go down. Bill would stay up late to check on us so I could relax. We explained this phenomenon by thinking that maybe my body temperature would somehow regulate theirs, or that maybe they too would relax and sleep more deeply because they knew they were being cared for. But could it be that my brain knew that I was healthy and this affected their mirror neurons?

My family had many examples of what we came to call “oooeeeoooeee,” chanted in the singsong tone of a creepy movie. When my oldest son has a problem, I feel it viscerally. One night I was reading in bed when I thought of my daughter visiting her new love. My body began to create the same mixture of joy and nervousness she must have been feeling, the joy of being with the man, and nervousness that this romance wasn’t going to work out. It was a strange feeling, one I hadn’t felt for 57 years. My aunt and I marvel that our letters often cross in the mail. We would discover that they had been written the same day. Now when I phone her, she will often say, with surprise, that she was going to phone me.

I know that my giving money to the man who had once lived in our neighborhood wasn’t because of my moral superiority. It was a visceral empathy, as if my own home were going to be taken away from me or the home of one of my children. Economist Jeremy Rifkin credits empathy brought about by mirror neurons for people’s rapid charitable response to the earthquake in Haiti

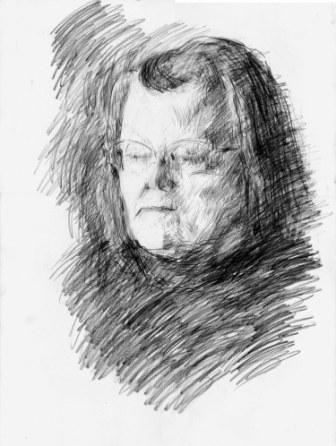

I wrote an Easter column about mirror neurons in conjunction with the Stabat Mater, a 13th century poem picturing Mary standing at the cross, feeling the pain her son was feeling. The poem has been set to music many times; it obviously resonates.

My calling has not been as a mystic or an eremite. I have been in the midst of family, society and the artistic community. I know, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that being in the world--family, society, community--is where I am meant to be even though I am often tempted to get out of it, having fantasies of selling all my possessions and presenting myself to the Rogersville Cistercian convent.

I’m indeed fortunate to have been surrounded by love my entire life. My father once said, “I have always loved extravagantly.” I have my mother’s passionate love letters to him. After she died, he said, “She thought I could do anything, and I didn’t want to disappoint her.” Near the end of his life, he would get up at seven and start drinking. Later the doctors told us that this was self-medication to alleviate the effects, mostly anger, of the strokes that no one knew he had been having. On a visit I would sit with him at the kitchen table all day, day after day. He disliked my leaving, even to go upstairs to the bathroom. Bill said that he would have another drink in the interlude, so I tried not to leave too often. After he went into the nursing home, I would stay there with him all day. I couldn’t bear to go home. I am weeping as I write this.