7. EXPERIENCING ART

The aim of an artist is not to solve a problem irrefutably, but to make people love life in all its countless, inexhaustible manifestations. Leo Tolstoy, letter

In the summer of 1968 Bill told his colleague Kent Thompson that I had been writing. Kent

One of these times was when a young David Adams Richards began to read The Coming of Winter, in his priest-like chanting voice.

In 1980, my friend and former McCord Hall member, Joe Sherman, asked me to write for the magazine ArtsAtlantic. He had newly taken over the editorship of the magazine and couldn’t find anyone in New Brunswick

[This essay] proposes that any coherent understanding of what language is and how language performs, that any coherent account of the capacity of human speech to communicate meaning and feeling is, in the final analysis, underwritten by the assumption of God’s presence. I will put forward the argument that the experience of aesthetic meaning in particular, that of literature, of the arts, of musical form, infers the necessary possibility of this ‘real presence’… To ask ‘what is music?’ may well be one way of asking ‘what is man?’…. “As I see it,” writes Ben Nicholson in reference to the works of George de La Tour… “painting and religious experiences are the same things, and what we are all searching for is the understanding and realization of infinity.” …. Yeats writes, “No man can create as did Shakespeare, Homer, Sophocles, who does not believe with all his blood and nerve, that man’s soul is immortal.”

George Steiner, Real Presences,

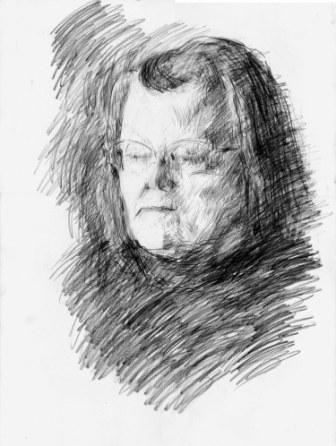

Pinned on the wall above my desk is a reproduction of Käthe Kollwitz’s crayon lithograph, Seed Corn Must Not Be Ground, the title a line from Goethe. A mother shelters her three children under her arms. The face of the mother shows fierce determination combined with fear, an exceptionally complex depiction of an emotion. One of the children has an expression of awe, another child an enigmatic smile. The anatomy of the mother’s arms is impossible but for that reason creates tremendous power. It’s one of my favorite works of art. Kollwitz created it in 1942, shortly after her grandson was killed in the war. It was her last print, done when she was 75 in defiance of the Nazis. Such a work could not be made without the hope that a belief in transcendence engenders.

Kollwitz had been warned many times by the authorities about her activities but was never imprisoned. One son had been killed in the First World War. Beside the lithograph I have pinned a newspaper photo of an Iraqi woman wearing a black abaya, crouched in a ditch in a similar pose, sheltering her two children under her outstretched arms. Her expression and those of her children are eerily similar to those in Kollwitz’s lithograph.

Jesus did use the metaphor of father to describe God—love, strength, protection--because mothers and their children are helpless in the face of war, rape, home invaders.